Once-in-a-Species

A groundbreaking new answer to one of humanity's big mysteries - and what it means about the nature (and future) of money

Humanity in art

It is often said that art makes us human. This notion becomes particularly interesting when we reach back to the edges of human history.

This is the Venus of Willendorf,1 a fertility goddess sculpture found in Austria that dates to 30,000 BP (years before present). For perspective, that makes this statue 6x older than the pyramids, 3x older than agriculture, and even 5,000 years older than light skin.2 The figurine’s proportions and cultural purpose may be mystifying, but it is unmistakably human art.

We also recognize the ancient figural depictions of animals on cave walls as something we might have done ourselves, if we lived as hunter gatherers. For example, these 30,000 BP3 drawings of Pleistocene megafauna from the Chauvet Cave in France.

Stepping back further in time, we similarly recognize ourselves in cave art. We are fond of the striking simplicity and humanizing power of hands on cave walls, etched timelessly in red ochre. For example, these handprints from Maltravieso, Spain that reach through time to proclaim “I was here, and here I lived.” In 2024, it was determined that these handprints date to 66,000 BP,4 making them the oldest known cave art in the world.

Just one problem… our species didn’t arrive in Europe until ~20,000 years after this art was made.5 Meaning, these hands belonged to Neanderthals. And yet, here they are, engaged in recognizably human art.

Why us?

For years now, a particular mystery has nagged at me. It started from an observation included in Nick Szabo’s outstanding “Shelling Out”.6 Since then, the significance of this question has snowballed in my mind.

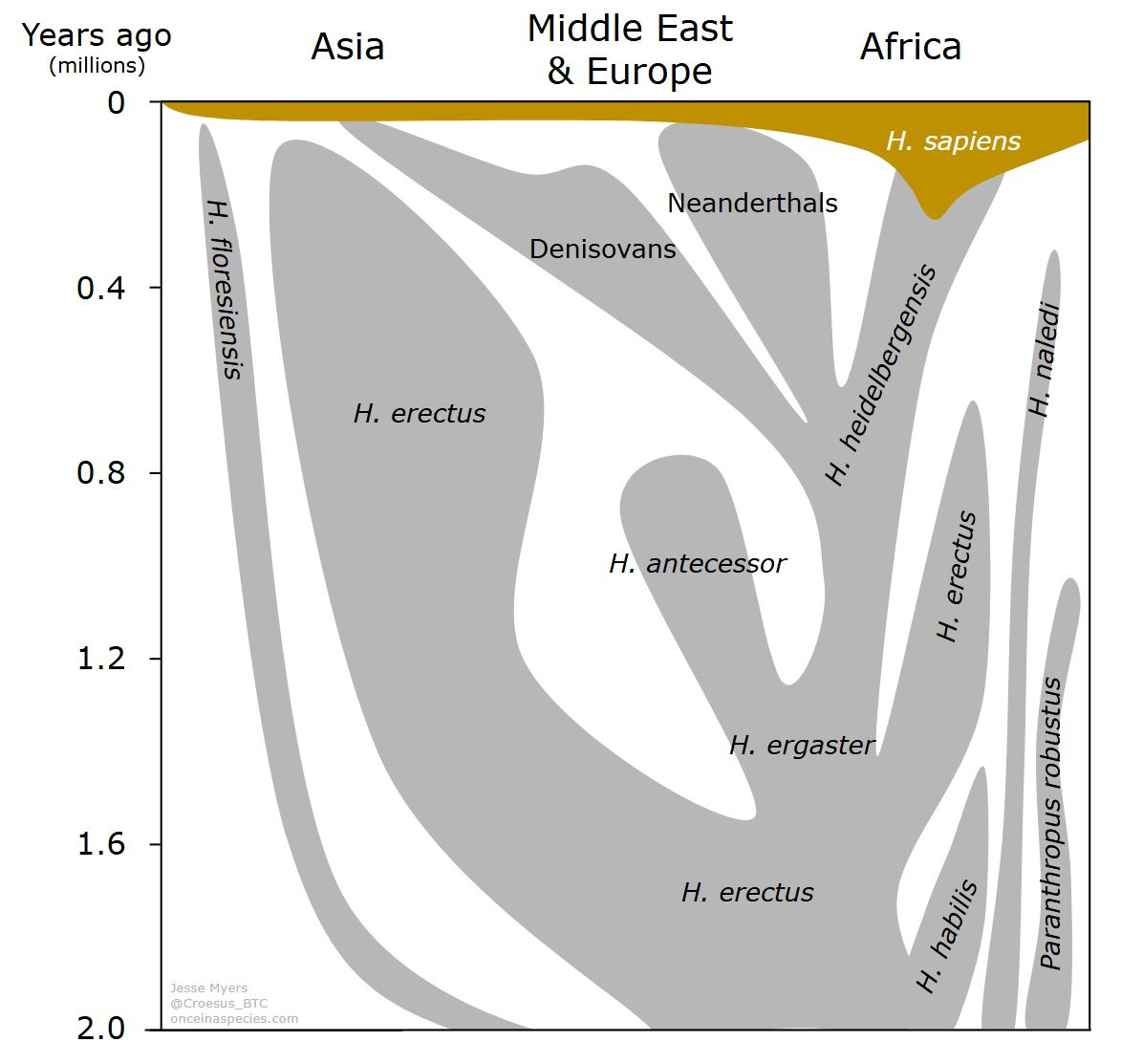

For upwards of a few million years, there were a handful of early human subspecies coexisting on our planet. In the blink of evolutionary time, now, there’s just one. Why did Homo Sapiens Sapiens (that’s us) triumph over all other early human subspecies?

Recently, a team of PhDs from Oxford argued that the answer to this question is that humans are “generalist specialists,”7 suggesting that we were able to thrive everywhere, and that this explains our success. Remarkably circular logic. Anthropology’s cutting edge answer provides no sensible root cause of humanity’s success; by contrast, this piece will.

By rendering recent discoveries in Anthropology and Neuroscience through the lens of a lesser-known branch of Economics, this piece puts forth an interdisciplinary answer to not only the question of “why did we triumph over other early human subspecies?”, but also to the grander question of “what defines our species?” Improbably, the answer to these questions can then be used to understand today’s ongoing financial revolution — the greatest seismic shift in the history of money.

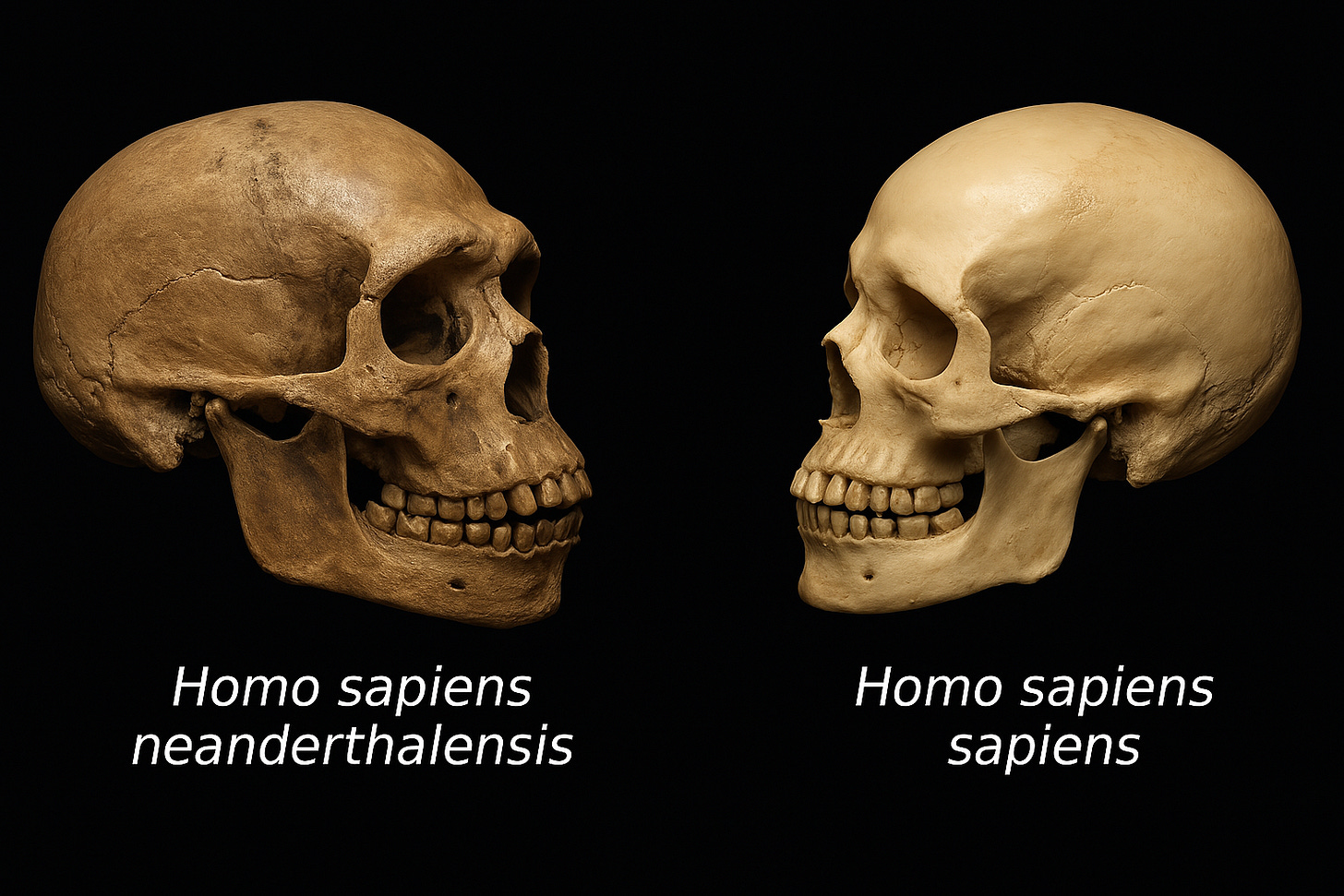

Neanderthals were humans, too

We are all familiar with Neanderthals. They’ve long been depicted with sloped foreheads and a dumb look on their face. The archetypical brutes; cavemen huddled around fires. From the beginning of our archaeological knowledge of this subspecies in 1856,8 we’ve needed an explanation for why they went extinct and we took over.

In classic Victorian fashion, the obvious answer was that we were smarter, better, more evolved. And for over a century, that has remained the prevailing view. But it doesn’t line up with the archaeological evidence.

In addition to engaging in art, there are other aspects of Neanderthals that were strikingly human. According to Chris Stringer, esteemed head of Human Origins research at London’s Natural History Museum, all of the conventional explanations for why we outcompeted the Neanderthals are wrong, including: “better tools, better weapons, proper language, art and symbolism, better brains.”9

In other words, the Neanderthal archaeological record does not reveal much difference between them and us. They would have lived lives much like us. They would have thought, felt, hoped, and dreamed. They may have even placed flowers on the graves of their dead.10 This is what artist Tom Bjorklund aims to evoke with his humanizing depictions of Neanderthals.

While Neanderthals may not have had smaller brains or worse tools, as we previously assumed, there had to have been some difference that caused Homo sapiens sapiens to outcompete. After 200,000+ years thriving in Europe,11 the Neanderthals were relatively quickly driven to extinction by the new arrivals from Africa. Why?

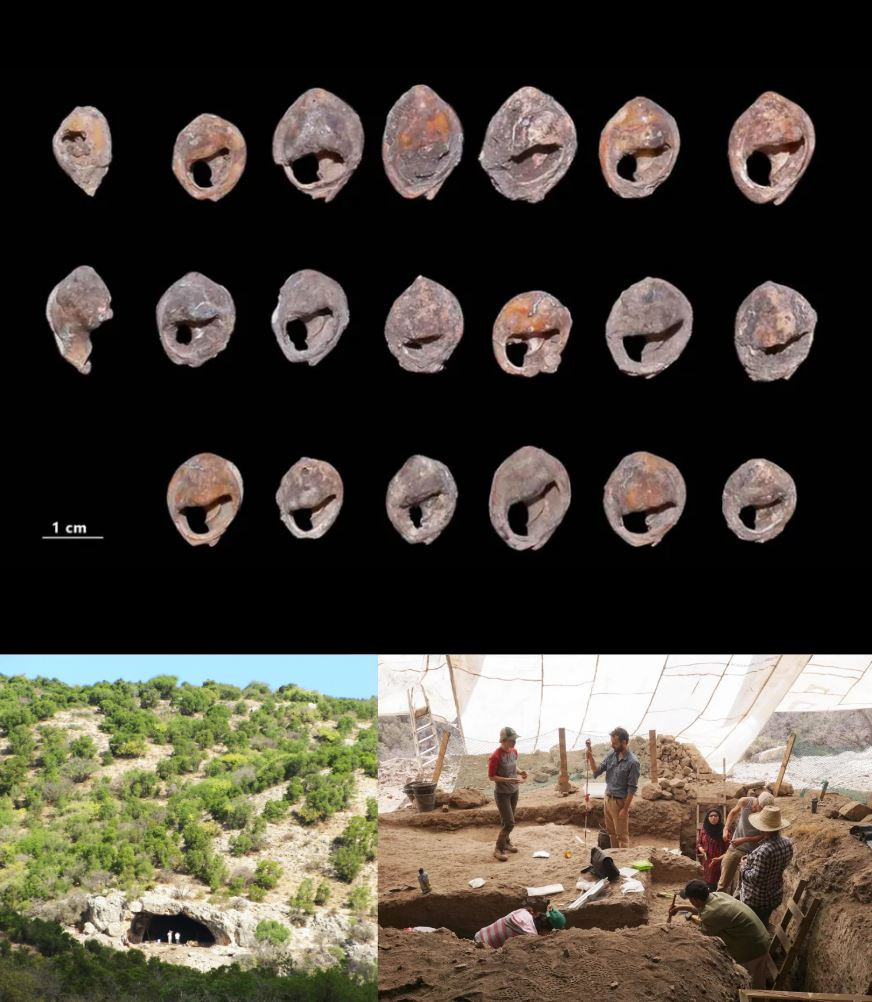

The history of shell bead jewelry

One thing that is quite clear from archaeological sites is that Homo sapiens sapiens collected shells and fashioned them into beads for necklaces and other jewelry. And we’ve been doing this for a very long time.

When Szabo published “Shelling Out” in 2002, the oldest evidence of this behavior dated to 75,000 BP12 at a cave site in South Africa. In the intervening years, even older discoveries have been made. Shell beads were discovered and dated to 82,000 BP,13 100,000 BP,14 and 120,000 BP15 at sites in North Africa and the Levant. In 2021, at a cave site in Morocco, 33 small seashell beads were discovered that dated to 142,000 BP.16

In just a couple of decades, our understanding of how long Homo sapiens sapiens have collected seashells to fashion jewelry has doubled, and it’s likely that older examples will be found still. It’s quite possible that this behavior began soon after our genetic divergence from other early human species around 300,000 BP (more on this later).

It’s also worth noting that these archaeological discoveries continue to be interpreted in accordance with the prevailing orthodox of Anthropology. The purpose and meaning of shell beads is described almost exclusively in terms of self-expression, status, and personal identity. For example, the co-author of the academic paper announcing the 142,000-year old beads speculates, “they were probably part of the way people expressed their identity with their clothing… wearing beads has to do with meeting strangers, you don’t have to signal your identity to your mother.”17

As an aside, this seems to be a clear example of how modern academia has become increasingly siloed in its respective areas of subject matter expertise. That’s particularly unfortunate with topics (such as this) that require interdisciplinary knowledge to make sense of complex human behavior.

Indeed, there’s no mention (or awareness) from the Anthropologists of the likely economic purpose of this shell bead jewelry. Instead, the same clueless co-author ponders, “It’s one thing to know that people were capable of making jewelry, but then the question becomes, ‘OK, what stimulated them to do it?’”

A peculiar differentiation

Before we answer the Anthropologist’s question, let’s first introduce an important observation about this behavior. While Homo sapiens sapiens actively (and prolifically) collected seashells and fashioned them into beads for jewelry, Neanderthals essentially did not.

When “Shelling Out” was written, we had not yet found any evidence of Neanderthal shell bead jewelry. Now, there appears to be a single example from a coastal cave in Spain.18 In addition, there are sparse examples of Neanderthals and other archaic humans collecting fossils, quartz, and other curios.19 This suggests that, intellectually, they had the capacity to recognize the specialness of uncommon materials, and even to engage in symbolic behavior (as we’ve already explored with cave art), but only on a limited basis. It’s not that they were incapable artists and craftsmen, just that they seem to have had a dim interest or drive to engage in these behaviors.

From the archaeological record, we can deduce that a Neanderthal walking on the sea shore would very rarely collect an ornate seashell. For us Homo sapiens sapiens, that’s almost unfathomable. Of course we would pocket the shell, take it home, and show it off. We appreciate a nice shell for its beauty, but also for its special rarity. Its scarcity. In a world of sticks and stones, wood and bones, it’s not often you come across a perfect shell. It does nothing for us, yet we appreciate and covet such things.

In this way, we are kinda weirdos.

And yet, this odd quirk appears to be the notable behavioral difference between Homo sapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Indeed, it may explain why we are here and they are not.

The hidden economic purpose of shell bead jewelry

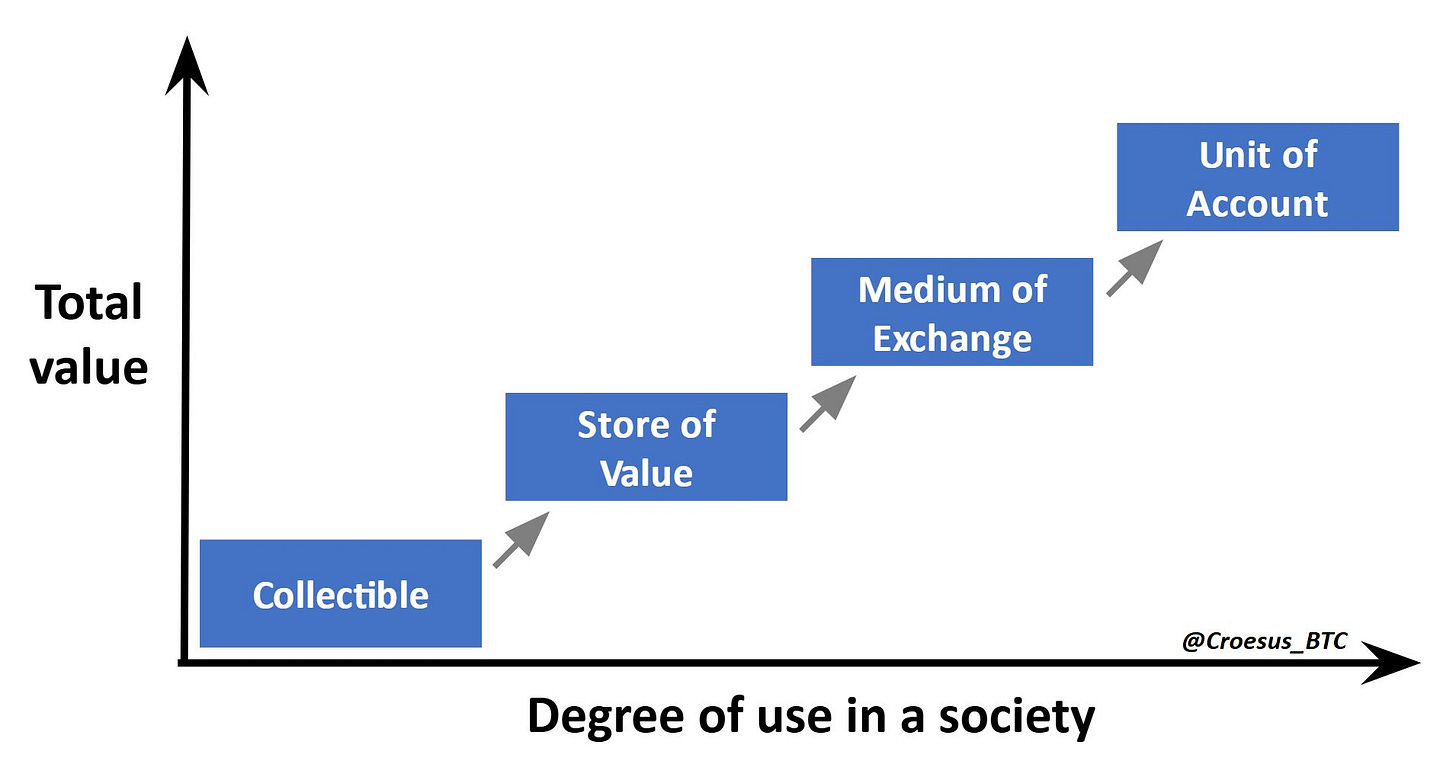

This is where familiarity with an arcane branch of Economics comes in. Austrian economists like Mises, Menger, and Hayek enumerated the properties and characteristics of commodity money. This meant studying gold and silver, but also earlier monetary mediums like glass beads, cloth strips, and seashells.

The Austrians observed that human societies all over the world landed on using suitable commodities as money — to transact with and to store value in for future use. They further identified the process by which a society ends up using a particular commodity as money.20

First, a commodity is appreciated by a small portion of the group and becomes a collectible. Then, the broader society starts to recognize that some of their peers value that commodity, and suddenly that commodity takes on inter-subjective value. Everyone knows that commodity is valued by some, so everyone knows it has market value, and therefore everyone begins to value it. As this process unfolds, the novel collectible begins to take on the properties of a store-of-value asset. Once the majority of a society values a store-of-value asset, it starts to be offered as a form of payment in trade. Now, the humble collectible has matured into a medium-of-exchange asset. Finally, once this commodity is the de facto currency for all trade, everything becomes priced in terms of that commodity — it is now the unit-of-account, or numeraire, for that society.

With this knowledge, our ancestors’ creation of shell bead jewelry is easily recognizable as a form of proto-money, as authoritatively shown in “Shelling Out.” The process of collecting seashells and turning them into jewelry would have been time and energy intensive. The product would have been impressive and valued — for its beauty but also for the costliness of its creation. As Szabo describes, necklaces or bracelets of shell beads could then be used to transfer wealth for important life events, like “injury compensation, peacemaking, tribute, inheritance, or marriage.”21

This mental model for shell bead jewelry provides considerably more explanatory power than Anthropology’s economically bereft consensus that this behavior, widespread across 100,000+ years, was simply because everyone likes to look good for strangers.

While Austrian economics reveals the behavioral purpose of shell bead jewelry as proto-money and further outlines the path-dependent process by which seashells grew to become money, what’s relevant for our purposes here is what sparks this process in the first place. Why do we value collectibles at all? For this, we turn to our final field of study.

The brain science of appreciating scarcity

Recent Neuroscience research has revealed a genetic difference between our subspecies and Neanderthals. In 2022, Pinson et al. published their findings about a single amino acid change in H. sapiens sapiens that differs from other early human subspecies, including the Neanderthals and Denisovans.22

The protein created from this gene (TKTL1) is involved in stimulating new neuron production in specific brain regions. In laboratory testing, the team was able to show that the mutated version shared by all modern humans (hTKTL1) caused greater neurogenesis in frontal higher-layer neocortical regions of the brain, as compared to the version of the protein shared by archaic humans and apes (aTKTL1).

Specifically, this mutated protein amplifies neuroprogenitor creation in the outermost layers on the front half of the brain (frontal lobe supragranular layers I, II, and III). When I did my undergrad studies in Neuroscience 15 years ago, these areas were well known for their unusual neuronal wiring, including pyramidal neurons and related association cortices. Pyramidal neurons link and integrate information across cognitive domains while association cortices synthesize and generalize this information into abstract thought.

With this recent discovery, we have a possible explanation for where these unusual neuron arrangements for abstract thought come from — an amino acid substitution (lysine to arginine) in TKTL1, achievable through a single nucleotide point mutation in the relevant section of Homo sapiens sapiens DNA.

We can also deduce when this mutation most likely occurred. Anatomically modern humans emerged ~300,000 BP in East Africa. Humanity’s most recent genetic bottleneck and matrilineal common ancestor, known as Mitochondrial Eve, lived ~160,000 BP, likely in East Africa.23 Given the facts, this mutation most likely occurred sometime between 300,000 BP and 160,000 BP.

What seems to have gone remarkably unappreciated by Anthropology is the functional Neuroscience of the affected brain regions, and how the resultant behavior change could make this single amino acid mutation a defining demarcation point in human evolution. In essence, this altered protein (hTKTL1) may have played a role in over-developing the specific brain regions involved in abstract thought, as compared to Neanderthals and other archaic human species. Importantly, this explains how we see occasional evidence of symbolic behavior (like art and collectibles) among archaic humans. The hTKTL1 change in our early lineage greatly increased the development of our abstract thought circuitry, and resulted in the creative explosion of culture seen with the global takeover of Homo sapiens sapiens.

In simpler terms, what this means is that modern humans are wired different. We may not have been any smarter than Neanderthals (as evidenced by similar tool sophistication and our slightly smaller brains),24 but we had a penchant for abstract thought. It seems likely that this single mutation drove the supercharging of symbolic behavior in our subspecies.

Neanderthals may have created occasional art, but Homo sapiens sapiens were compelled to create much more. But where this seems to have really mattered was with respect to having the capacity to appreciate and value scarce commodities.

This over-developed brain wiring supercharged our interest in scarce assets and our drive to obtain them. Behaviorally, this may have amounted to making us weirdos who collected seashells, simply because we couldn’t help but value their special rarity. But as we’ll explore, that odd behavioral quirk may have made all the difference for our species.

The foundational building block of human flourishing

The other clear disparity between early modern human cave sites and Neanderthal cave sites in Europe is the population density. When Homo sapiens sapiens took over an area from Neanderthals, they were somehow able to support 10x the population on the same territory versus the prior Neanderthal inhabitants.25

This has long been considered a curious fact without a tidy explanation. But the explanation has been right under the nose of the Anthropologists: shell money. The widespread presence of shells at Homo sapiens sapiens cave sites suggests that we had already developed the concept of money by the time we arrived in Europe ~45,000 BP. And this innovation allowed for much larger social groups.

In 1992, Robin Dunbar published “Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates,” concluding that humans have the capacity to maintain stable social relationships with 150 individuals — now famously known as “Dunbar’s number.”26 A year later, he published a follow-up paper that added language (and social gossip) as an efficiency multiplier that allows humans to manage bonds in 150-person tribes, without having to spend almost half the day engaged in one-on-one socializing.27 But this still doesn’t account for how humans do manage to live in populations much larger than 150. An additional efficiency multiplier neatly resolves this conundrum: the concept of money.

In a barter system of goods and favors, a social group can only reach ~150 individuals before the number of interpersonal relationships becomes too numerous to keep track of (note: that’s 11,175 relationships, based on combinatorial math). At this point, the individual ledgers of personal debts between counterparties become impossible for the rest of the group to help police.28

In other words, a society without money can only function if it stays limited to Dunbar’s number of 150 people — a tribal existence. Note that within this moneyless paradigm, inter-tribal relations would be generally antagonistic, with the benefits of barter overshadowed by unending grudges and blood feuds, devoid of a mutually-agreeable means of peacemaking between tribes.

By contrast, if you have the concept of money, you not only are freed from the constraint of interacting chiefly within a closed group of 150, but you also gain the necessary transactional medium for constructive inter-tribal relations.

First, with the concept of money, goods and services can flow and be paid for at the time of transaction between an infinite number of counterparties, fostering rudimentary capitalism. Money removes the need for the tribe to help police the mental ledgers of debts and favors between all counterparties, which may be the primary constraint that Dunbar’s number actually captures.

Second and perhaps more importantly, with the concept of money, multiple tribal groups can coexist in close proximity. In the same way that money can be transferred between individuals within a group for important events like injury compensation, peacemaking, and tribute, it can also be transferred for the same reasons between tribal entities.29 Thus, money provides a transactional medium for constructive inter-tribal relations, as a new option alongside time-honored violence.

Equipped with money, tribes can more easily engage in trade, as well as negotiate and maintain mutual-security alliances. In turn, these benefits naturally foster the development of super-tribal groups living in close proximity, thereby achieving 10x the population density of other early human subspecies. The coordination of such large, multi-tribe populations would constitute a clear advantage when competing for resources against solitary tribal units of Neanderthals or any other archaic human species.

Ultimately, this means that having the concept of money was the essential differentiator that allowed our subspecies to proliferate. And as we’ve explored, it’s also the key ingredient that enabled large scale population coordination to develop. Therefore, appreciating money is the foundational building block of human civilization, and consequently, of human flourishing.

While Neanderthals and other archaic humans had the basic brain circuitry necessary for abstract thinking (as evidenced by occasional art and collectibles), this latent capacity was evidently insufficient. A certain threshold of covetous interest in scarce collectibles is necessary to bootstrap the concept of money in a social group. Neanderthals and other archaic humans lacked the brain circuitry to achieve this critical mass.

And herein lies the answer to our question. The reason that Homo sapiens sapiens outcompeted all other human subspecies is that we are wired differently, and as a result, we have an exaggerated capacity to appreciate and value commodities that are hard to come by. In other words, we are wired to cherish (and covet) scarce collectibles, like seashells.

This charming quirk is actually the basis for our overpowering evolutionary advantage, as it enabled our species to bootstrap the concept of money. In turn, this unlocked capitalism and enabled the large-scale coordination of interests that we call civilization.

It turns out that it’s not art that makes us human.

Instead, our fascination with scarce assets is what makes us human.

Fulfilling a species-long quest

Whereas modern Anthropology has offered up circular logic as an answer to this question — one of humanity’s great mysteries — we have now laid out a cogent and complete alternative. Humanity’s triumph is likely due to a single amino acid mutation between 300,000 - 160,000 BP supercharging our brain centers for abstract thought, allowing for the critical mass of interest necessary to develop the concept of money, and leading to our overpowering competitive advantage of multi-tribe population coordination unbounded by Dunbar’s number.

At this point, we’ve been entirely focused on humanity’s distant past and our defining behavioral advantage over other early human subspecies. But now, we would be remiss not to take these lessons of the past and apply them to understand a phenomenon of the present.

Inevitably, we turn now to Bitcoin.

The history of money in human civilization is characterized by an ongoing process of upgrading from one form of money to a fitter, more scarce form of money. This selective pressure of monetary Darwinism stretches back at least 142,000 years, and likely much further in our 300,000-year history. With gold’s emergence as a viable store-of-value asset in the Danube valley ~6,000 BP (because of the Varna culture’s advances in metallurgy),30 the modern history of money has been characterized by the conquest of gold over all other monetary local optimums around the world, specifically because of its unmatched physical scarcity.31

But with the dawn of the digital age, it became possible to create a commodity more scarce than gold.

Bitcoin was deliberately designed to solve for gold’s weaknesses (e.g., the challenges of assaying, transporting, and securely storing a physical asset) and to improve on gold’s strengths.32 Most importantly, Bitcoin perfected scarcity. For the first time in human history, there is a form of money with immutably finite supply — the invention (or discovery) of absolute scarcity.

If you put Bitcoin in the long timeline of human history, it is the perfection of our species’ defining fascination: scarce assets. Just 16 years into its existence, we are witnessing the ongoing and inescapable gravitation of all Homo sapiens sapiens to this perfection of store-of-value scarcity. We can’t help it, it’s quite literally in our DNA to appreciate and value scarcity.

With this context, it’s no wonder that people who learn about Bitcoin become insufferably zealous about it — this is what we’ve been searching for for over 142,000 years!

Valuing scarcity is what differentiates us as a species, what makes us human. Which means that absolute scarcity is the ultimate fulfillment of our species-long quest for better scarcity.

After ~12,000 generations of mankind, somehow, we are lucky enough to be alive during this monetary transition to perfect scarcity.

This only happens Once-in-a-Species.

Neugebauer-Maresch, N. A., et al. The microstructure and the origin of the Venus from Willendorf. PNAS (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8885675

Juzeniene, J., et al. Skin colour and vitamin D: An update. Experimental Dermatology (2021). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/exd.14142

Wilford, J. T. Finally, the Beauty of France’s Chauvet Cave Makes its Grand Public Debut. Smithsonian Magazine (2014). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/france-chauvet-cave-makes-grand-debut-180954582

Maltravieso Cave Hand Paintings. All That’s Interesting. https://allthatsinteresting.com/maltravieso-cave-hand-paintings

Cunliffe, B. (Ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press (1994).

Szabo, N. Shelling Out: The Origins of Money. Nakamoto Institute. https://nakamotoinstitute.org/library/shelling-out

Brodwin, E. Why Homo Sapiens Beat Out Every Other Human Species. Inverse (2018). https://www.inverse.com/article/47597-generalist-specialist-homo-sapien-adaption

Scarre, C. (Ed.). The Human Past (4th ed.). Thames & Hudson (2021).

Lu, D. What’s the Difference Between a Human and Neanderthal Brain? Smithsonian Magazine (2022). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/whats-the-difference-between-a-human-and-neanderthal-brain-180980736

Will, M., et al. A morphometric assessment of Late Pleistocene human mandibles from the Levant. Journal of Archaeological Science (2023). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440323001024

See note 8. (The Human Past, ed. Chris Scarre.)

Hublin, J.-J., et al. Radiocarbon dates from the Grotte des Fées and implications for the disappearance of Neanderthals. Science (2012). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1221354

Vanhaeren, M., et al. Middle Paleolithic shell beads in Israel and Algeria. PNAS (2007). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0703877104

Wong, K. Ancient Shell Beads Could Be World's Oldest Jewelry. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ancient-shell-beads-could

Bar-Yosef Mayer, D. E., et al. Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel. Journal of Human Evolution (2009). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047248408002340

Sehasseh, E. M., et al. Early Middle Stone Age personal ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco. Science Advances (2021). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abi8620

Greshko, M. World’s Oldest Jewelry Discovered in Moroccan Cave. Smithsonian Magazine (2021). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/worlds-oldest-jewelry-discovered-in-moroccan-cave-180978766

Hoffmann, D. L., et al. Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals 115,000 years ago. Science Advances, 4(2), eaar5255 (2018). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aar5255

Moncel, M.-H., et al. Non-utilitarian objects in the Palaeolithic: Emergence of the sense of precious? Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia (2012). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230703161

Menger, C. On the Origins of Money (1892), translated by C.A. Foley. https://www.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3ll3/menger/money.txt

Szabo, N. The History of Money. Bitcoin 2021 Conference. YouTube.

Pinson, A., et al. Human TKTL1 implies greater neurogenesis in frontal neocortex of modern humans than Neanderthals. Science (2022). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abl6422

Landau, E. Mitochondrial Eve: Common Ancestor Lived 160,000 Years Ago. Medical Daily (2013). https://www.medicaldaily.com/mitochondrial-eve-common-ancestor-all-humans-actually-lived-160000-years-ago-244742

See note 5. (The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe, ed. Barry Cunliffe.)

Mellars, P., & French, J. Tenfold Population Increase in Western Europe at the Neandertal–to–Modern Human Transition. Science (2011). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1206930

Dunbar, R. I. M. Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469–493 (1992). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/004724849290081J

Dunbar, R. I. M. Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681–735 (1993). https://pdodds.w3.uvm.edu/files/papers/others/1993/dunbar1993a.pdf

See note 6. (Shelling Out, Nick Szabo.)

Ibid.

See note 8. (The Human Past, ed. Chris Scarre.)

Ammous, S. The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. Wiley (2018).

Boyapati, V. The Bullish Case for Bitcoin. Bitcoin Magazine Books (2021).

This is brilliant. First, you named your Substack "Once-in-a-Species," referring of course to Bitcoin. I'm sure most people thought you were being a little hyperbolic.

But then, years later, you came up with a novel set of insights to fully justify it. How sweet is that?!

Lots of work went into this Jesse and I appreciate you sharing it. Very plausible and captivating.

Not only do we appreciate scarcity, we penalize fraud, plagiarism and counterfeiting because we are programmed against it.

So not only have you explained our fascination with Bitcoin, you have explained bitcoiner’s aversion to altcoins!! Great stuff