#66.1: A response to my charts on the All-In Podcast

What Chamath gets wrong about the US National Debt, deficit spending, and Bitcoin

On Friday’s episode of the wildly popular “All-In Podcast,” the panel of extremely successful Silicon Valley investors discussed several of my charts from “Once-in-a-Species.”

Today’s post will be addressing the juiciest part of that discussion — the ~2 minutes from this starting point:

It was a small thrill to see my charts discussed on such a big platform, but that sense of pride quickly gave way to a more complex mix of righteous frustration and thoughtful circumspection at Chamath’s position on the US National Debt.

Before we get into what Chamath gets wrong, these are all the charts they talked through (here is the relevant video timestamp if you want to see that full discussion):

All of these charts are from a recent edition of this newsletter. If you didn’t catch that recent piece, here it is:

Okay, with that context provided, now let’s get into it…

What Chamath gets wrong about the US fiscal situation

Chamath’s objection takes a free-form, meandering course (understandable on a podcast), so here is my effort to synthesize his main arguments into what I hope is a fair characterization:

The US National Debt isn’t a problem because:

Demand for US Treasuries is showing no shortage of strength

The US can always refinance the debt at longer duration maturities

Worrying about US National Debt default is a long-tail outcome (<0.1% probability) not worth focusing on — it’s “a nothing”

Balancing the budget is doable if we focus on the right lever:

Spending cuts won’t happen

Reducing tax receipts can impose responsible spending because politicians will have less money available to spend

Deal with the US fiscal position as it stands — your choices:

Bet on American exceptionalism & US GDP growth to take care of the US National Debt in time, or

Bet against America’s fiscal future and leave the country

These are interesting and somewhat compelling arguments, however, I believe Chamath is fundamentally viewing this from the POV of “the system is fine.” Frankly, this is understandable, as the system has been extraordinarily good to Chamath, so where’s the problem? (A theme I explore at length in the article I’m best known for.)

In terms of addressing what Chamath is missing, I’ll reflect the structure of the argument above…

#1 - US National Debt outlook:

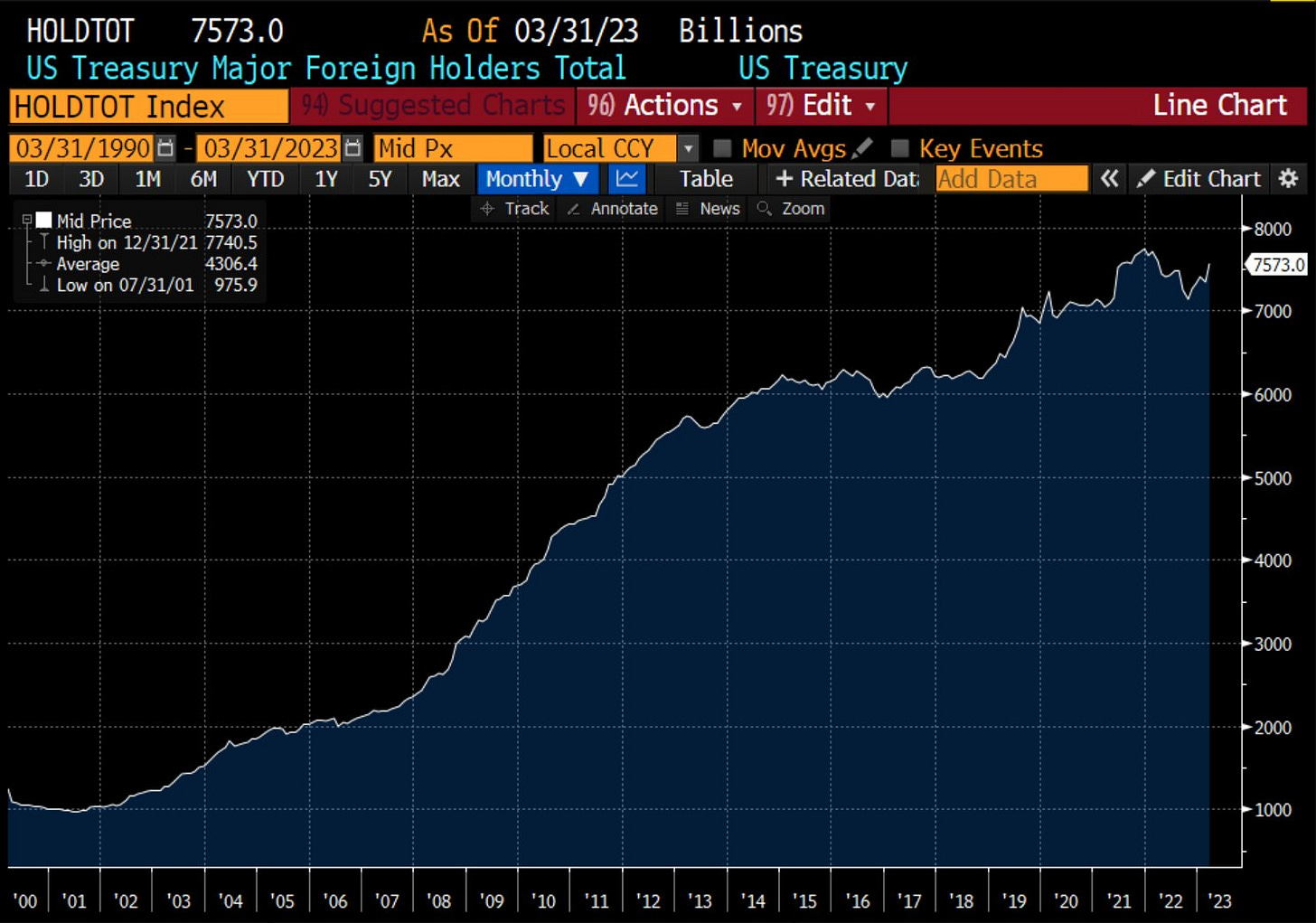

Countries are buying more US Treasuries in nominal terms, but fewer as a % of total debt (the more relevant measure)

At the end of the day, USTs are contracts promising to pay a modest nominal yield every year for their duration. That works out great for everyone, so long as that yield is greater than inflation over the same period. But that’s not an attractive proposition if you think the issuer’s balance sheet has deteriorated to a point that they will print money to soft default on that debt.

Chamath suggests just re-financing loans for even longer duration. Great idea from the POV of the US. But any buyer is a sucker purchasing a one-way ticket to wealth destruction in real terms. Might as well call them War Bonds.

This isn’t a long-tail outcome, as Chamath frames it to be

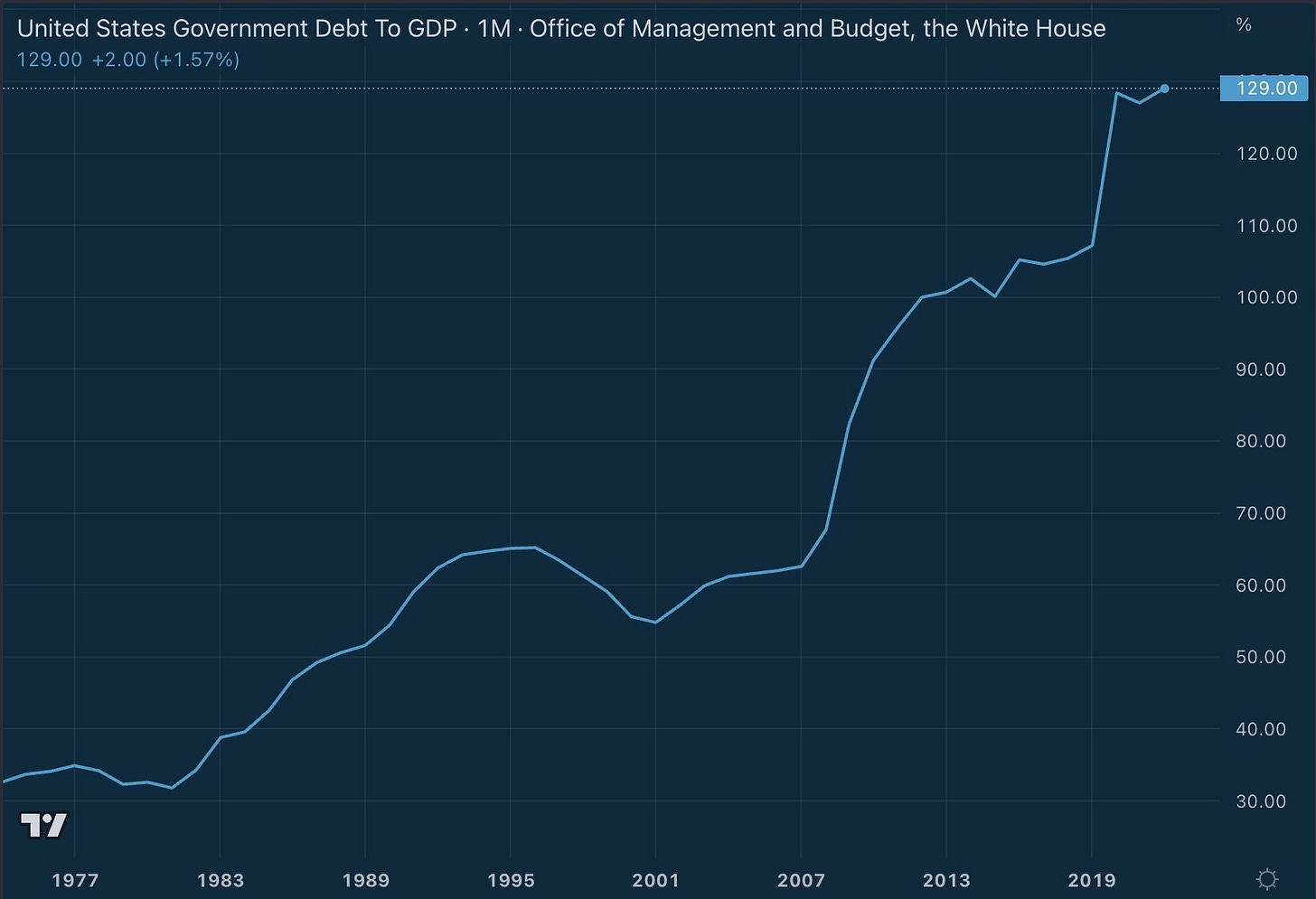

Since 1800, 51 out of 52 times a government has reached 130% debt-to-GDP, they eventually defaulted in some manner.

The only exception is current Japan, deep in the final stages of circling the drain (e.g., yield curve control and central bank balance sheet expansion).

As of now, the US is at 129% debt-to-GDP.

This isn’t “a nothing” — over the coming decades, holders of US debt stand to lose the wealth they’ve stored in the world’s “risk free” asset

The points above mean that if the US continues to run spending deficits (they will — currently on track for a ~$2.2T deficit in 2023), the US will cross into territory that no country has come back from without defaulting in some form.

Defaulting comes in two varieties — hard default (re-negging on the debt completely) or soft default (printing a ton of money to service the debt in nominal terms, while re-negging in real terms)

The US soft-defaulting would mean the partial destruction of purchasing power for $31.5T of US bonds. That’s the core of the “fixed income” market. And that means pensioners and retirees, many of whom shift from the classic “60% equities / 40% bonds” portfolio to a “conservative” “20% equities / 80% bonds” portfolio to live out their hard-earned retirements.

#2 - Balancing the national budget:

Chamath mentions that spending cuts don’t happen. He’s right on this point!

However, then he says that the solution is to reduce tax receipts so there’s less money available to spend. Great in theory, but in truth, that’s the whole problem we’re already facing:

We have normalized massive deficits as politically acceptable over the last 22 years. We don’t have the tax receipts to spend, but that hasn’t stopped us from spending anyway. And where does that money come from?

Deficit spending, which means taking on more debt. To deliver a positive real return to those debt holders, future generations have to pay the bill for today’s spending. The only other alternative is that we don’t deliver a positive real return on that borrowing, which means soft defaulting — and now we’re back to the inescapable math of the US National Debt.

#3 - If you don’t like it, leave:

Chamath asserts the moral high ground, chastising that everyone should bet on American exceptionalism or “don’t fucking be here.”

American exceptionalism:

It’s true that no country on earth better enables capitalism to flourish through the entrepreneurial actions of individuals. America’s founding design is unparalleled in that respect — that’s American exceptionalism.

However, I believe that same American exceptionalism has been clouded over by the scourge of fiat money in the last 50 years.

The ability to print money and tamper with interest rates has warped the organic processes of capitalism — sallowed the healthy glow of American exceptionalism.

The Cantillon effect and its beneficiaries

The Cantillon effect — named for the economist who first outlined it in the early 1700s — details the inequity of money printing disproportionately “financing the financiers”.

The modern debt-fueled fiat monetary system is the Cantillon effect in its purest sense. Money printing (whether direct stimulus by central bankers or M2 money creation via commercial bank lending) has been exceptionally advantageous to financiers. While the middle class has eroded into abject despair since 1971, the modern financiers have thrived. Call it the rich getting richer, call it profiting from globalism — no matter how you cut it, it’s fueled by the Cantillon effect.

One archetype that has found an extraordinary amount of success in this system is the Silicon Valley venture capitalist. These modern financiers have found an edge at navigating and exploiting this fiat landscape for personal enrichment through exotic vehicles like the SPACs that Chamath is known for — “winning” as some would call it.

While VCs are not to blame — “don’t hate the player, hate the game” — the result of the debt-fueled fiat monetary era has been the draining of American pre-eminence and credit, straight into the coffers of private interests.

Leaving faux capitalism in favor of genuine capitalism

It may sound radical to say, but I believe that everyone should metaphorically opt out of this sickly version of America, altered from the founding vision of capitalism and honest money.

Not leave in the literal, physical sense. Instead, in the monetary sense.

The fiat monetary system undermines the American endeavor because it warps capitalism in favor of the financiers who sit closest to the money spigot, at the expense of everyone else just trying to do their job and save for the future.

To leave this version of faux capitalism simply requires switching from saving in a fiat-based money to a hard money that cannot be printed. In doing so, people can opt into a return to American values of hard work, reliable savings, and thoughtful capital planning.

I realize this sounds like a leap, but that is the promise of Bitcoin. And luckily, I believe Bitcoin is on an unstoppable path to assume this role in the average person’s life over the coming decades, simply because of its superior properties that serve the interests of savers (instead of those who currently benefit from the Cantillon effect).

With enough time, those properties will be evident to all - it’s a process in motion, as Bitcoin relentlessly moves from the anarchist libertarian fringe into the mainstream consciousness to become the most important asset of the 21st-century portfolio.

That’s what I think Chamath gets wrong on the US National Debt and fiscal position.

In the course of reflecting on Chamath’s views, I couldn’t help but also marvel at the fact that he is a large Bitcoin holder. These facts are somewhat incongruent, as we’ve now established that betting on Bitcoin is metaphorically hedging against the version of fiat capitalism that Chamath so proudly defends.

For paid subscribers, I’ll now share:

The story of how the Winklevoss twins acquired a large Bitcoin position

The story of how Chamath acquired a large Bitcoin position

What these stories reveal about how little some of the largest holders of Bitcoin know about the asset

One of the remarkable things about many of the largest holders of Bitcoin is that they don’t understand Bitcoin. But they don’t need to. All they need to understand is a large enough morsel — some elevator pitch of the investment case for Bitcoin.

The Winklevoss twins

The Winklevii famously learned about Bitcoin at a party in Ibiza in 2012, while celebrating their legal victory over Zuckerberg. Flush with millions from their settlement over the origins of Facebook, the Winklevii were looking for compelling investments.

They looked into Bitcoin and quickly understood that Bitcoin could serve as a kind of digital gold. Back then, Bitcoin was trading at $11/coin. If Bitcoin was to eventually match gold in terms of total valuation, that would mean $400k/BTC. That’s a very clear and hugely asymmetric bet.

That was enough for the Winklevii to bet millions on Bitcoin and hold on through the volatility of the last decade, becoming extremely wealthy along the way.

But it didn’t mean they fully understood Bitcoin — they just understood it well enough.

The truth is, “digital gold” is a small subset of what Bitcoin is on track to become. It’s more than that — Bitcoin is the one-time invention of absolute scarcity and stands poised to siphon much of the value parked in inferior store-of-value assets (Bonds, Real Estate, etc.).

The Winklevii don’t believe in that singular significance of Bitcoin in the digital asset landscape, but they haven’t needed to. As a result, the Winklevii have dabbled in other cryptocurrency offerings, just as many (if not most) early Bitcoin adopters have.

Being early to Bitcoin doesn’t mean that you understand Bitcoin, though it generally means you (and the general public) think you do.

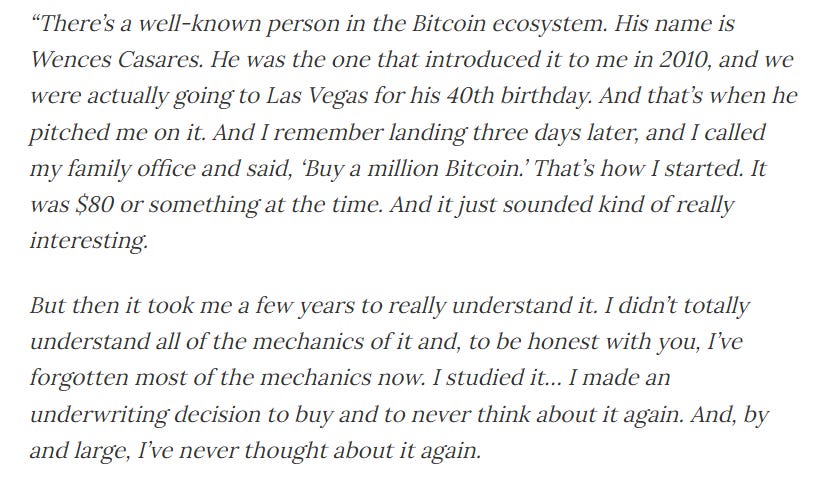

How Chamath became a large Bitcoin holder

I began with the Winklevoss twins’ story because it is no different from how Chamath became a large Bitcoin holder.

Chamath heard about Bitcoin on a private jet flight to Las Vegas. He happened to be traveling with famed Bitcoin evangelist, Wences Casares. Here’s how Chamath told the story in a 2020 interview:

A few points worth mentioning:

Bitcoin was not $80/coin in 2010. It wouldn’t reach that price until 2013

It wouldn’t be possible to buy 1 million Bitcoin in 2010, as there weren’t even formal exchanges at that point, and nobody would have been able to accumulate ~1/4 of the total Bitcoin supply in existence at that early date via the secondary market. We don’t know how large Chamath’s position is, but it’s much less than 1 million Bitcoin

Chamath acknowledges that he didn’t fully understand Bitcoin, and has forgotten most of what he understood when he did his diligence in 2010

Fundamentally, Chamath’s investment in Bitcoin was rooted in what information was available in 2010, and it was fed to him via the filter of Wences Casares. Wences is known as “Patient Zero” for Bitcoin adoption in Silicon Valley because he persuaded Bill Gates, Reid Hoffman, and many others to acquire a Bitcoin position.

Wences understands Bitcoin at a deeper, more visceral level because he is an Argentinian tech entrepreneur who witnessed firsthand the effects of high inflation in the 1980s, 2000s, and 2010s. Wences knew the value proposition of Bitcoin enough to evangelize its importance, and he honed his messaging to whatever resonated with technology investors — some variant of the “digital gold” thesis that the Winklevii latched onto.

That was enough to convince Chamath to become a large Bitcoin holder, despite the fact that he clearly doesn’t understand what he holds.

This is particularly ironic because to bet on Bitcoin is to hedge against Chamath’s favored version of America — the highly financialized version of everything where stock market operators are the rockstars of the moment.

Chamath feels strongly that people who aren’t betting on the continuation of our debt-based monetary system should leave… yet he is a large holder of the best instrument for betting on its collapse.

To resolve this unseemly dissonance, perhaps he should put his money where his mouth is and sell his Bitcoin.

Awesome piece Jesse, as always. And thank you for listening to Chamath for me so I don't have to.

My favorite part is your statement here: "I believe that everyone should metaphorically opt out of this sickly version of America, altered from the founding vision of capitalism and honest money. Not leave in the literal, physical sense. Instead, in the monetary sense."

I hope Chamath sells his bitcoin. He is clearly a villain in the bitcoin story